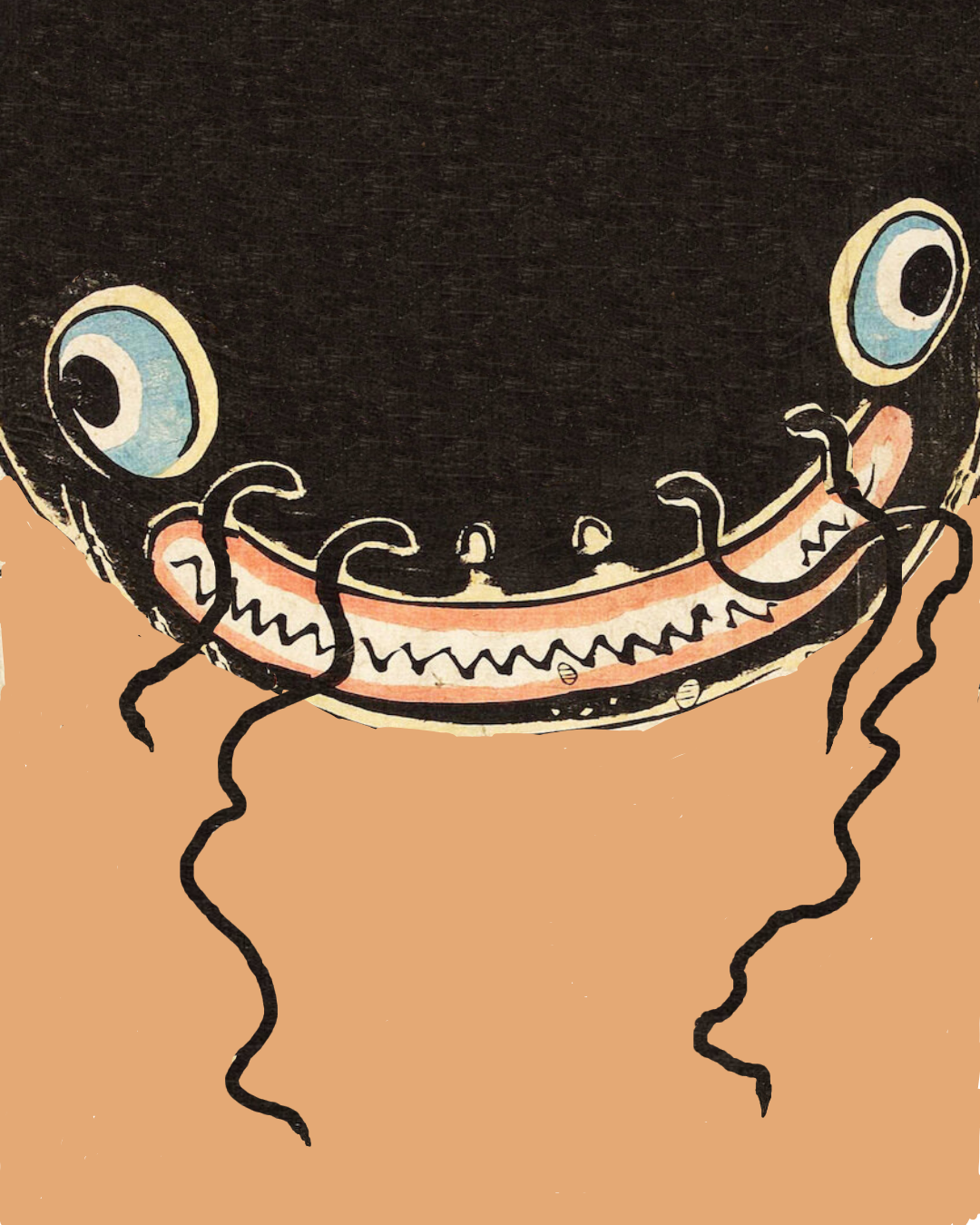

The Magoor

Illustration by Aneendya Datta Gupta

This story is published in collaboration with Centre for Contemporary Folklore.

The winds had come, uprooting the trees, the ageing bamboo fences, and even the roofs of some houses. It signalled the end of winter, but the rain hadn’t arrived yet - the rain that would rejuvenate Sibo-Korong into a stream again. At times, the stream would eat into the fields on its periphery, moving humongous boulders from the mountains and rolling them so vigorously that they turned into small, smooth pebbles and scattered the rocks in its path. The stream originated in the lofty hills and ended its rocky trail at the mouth where it met the Siang - a name the locals of Pasighat know the Brahmaputra by.

This desolate state was the opposite of the lively spirit the stream carried during the summer season when it brimmed with foliage and chattering water currents. Schools of fish swam across this stream, enjoying the season of merrymaking, dancing as they jumped out of the water, turning into glimmering silver coins that attracted the eyes of fish enthusiasts. The river now was nothing like the summer months - its rocky trail resembled a dried scalp, chafing white powder on the rocks, the glow once polished by water and school of fish, gone.

The water that remained pooled into deep and shallow puddles. These had accumulated during summers and stayed through the winter, turning dark green with algae outbursts, fertilised by sweat, soap, and detergent from countless overworked migrant workers who were compelled to wash and bathe there.

What was not stagnant flowed in thin, veiny water channels that emerged from groundwater springs, tucked into the crevices of eroded hills. Some hills were forever gone - their traces scattered across the river's path. Glimmering granules of sand swapped by shards of glass, and piling plastic waste along the stream. No one to clean it - only the sand mafia who cleaned, but took away much of the river’s sand.

The Riverbed was scraped raw, now smothered in waste. It was rotting, but the remedy was nowhere to be found.

The rains weren't arriving. They were late—much later than last year when the rains had lingered too long, disturbing the crop cycle and reducing the rice production, the sole staple of the region. This year, it seemed that the rain wouldn't grace Pasighat.

Only fragments of water remained on the rocky skeletal trail of the Sibo-Korong - a river so named because two lovers had drowned themselves in a bygone era. Sibo or “die-together” and “Korong” connoting a stream or river. This “die-together” river, with its annual outburst during the monsoon, and body marked by stores of water, was drying fast. The deep pools were shrinking, and most of the puddles were already gone. The fish and other creatures that lived there were eaten by predatory birds that flew over the trail. Each year, the morsels turned meagre, the birds finding it difficult to manage, as food became less for them, the search became more impatient and longer.

Sibo-Korong was dying alone - thinning, fading, and it seemed unable to meet Siang this year.

But this year, the birds also feasted on a pool that had never dried before: The sacred grove of Sita-Pong, where a female water spring spirit once lived. This benevolent being had charged the pool for years, till she met a tragic end. The grove had been burned, the wild colocasia plants uprooted, and the ground dug to reclaim sand for construction. And when the reclamation ended, the area became the dumping ground for waste from the newly extended peri-urban college settlement.

A catfish, whose long-gone ancestor was the son-in-law of the benevolent spirit, had been given permission to settle in Sita-Pong. So, the lineage of these Mítdong Catfish, or the one with long whiskers, had lived there as crafty descendants of an enterprising resident son-in-law. Now, only one catfish remained.

/// \\\

In the ever-shrinking pool, the last Mítdong moved constantly, digging into the earth to make a depression, so it could hide from the predatory birds that were waiting for the remaining water to dry. It struggled hard and performed the last rites of the water spirit and other creatures whose bodies it protected from the birds. Before dying, a shrimp had instructed the catfish to reach the Siang through the remaining thin, veiny water channels before they also completely died out. The catfish sang the hymn of mourning, repeating it as it buried the many corpses with altars and grave goods. But even in death, the creatures of Sita-Pong were to live in pollution forever; Soon after, the waste trucks came and dumped garbage over the burial site. As the sun set, making way for the moon to take her place, the catfish looked upon the desecrated land and decided that it would leave Sita-Pong, a home which it had never left. Others had left before - the shrimps and smaller fish had gone out of the grove to barter algae for white silt from creatures in the Siang. They had told him about the endlessness and vastness of the Siang, and now it only saw hope in moving from this place, which no longer resembled his home.

The catfish jumped out of the hole it had dug in the remaining waters of the Sita-Pong pool and landed in the puddle next to it. From there, it had to crawl through broken shards of glass— a remnant of the grove's destruction. This caused numerous cuts into its slippery body, wounding it as it crawled.

Eventually, it encountered a channel of water that furthered its course; crashing the fish onto a rock and banging its head. In pain, the catfish continued its journey, now reaching the shadow of tall concrete pillars. The catfish thought big fireflies were flying on them, but they were cars running across the Sibo-Korong bridge.

The fish could also hear the loud shouts of men on the bank of the dried river, who were dancing in rhythmic circular fashion, imitating the Ponung dance, pausing for arguments, then collapsing around a bonfire drunk.

One of the men stumbled towards the path on which the catfish was crawling, to urinate — and his urine, reeking of booze, fell on the fish’s wounds. It burned, and the catfish shrieked and yelled in deep agony. The man was alerted by the strange feeble sound and fell back —“It is…a sn…snak…snake!” he screamed and ran back towards the bonfire.

The catfish writhing in agony hurried to escape this scene, only to find itself trapped in a nylon fish net. The net entangled its gills, a struggle so intense the slime on its body dried out. As it moved ahead, its body gave up on producing the slime, the glands were mutilated but now he was free from the trap.

It then swam through an eerily quiet water channel and found itself amongst countless bones of fish that had died on this trail. Yet again, it had to keep on crawling, this time on the fine, grainy sand. As it completed the crawl, the sun rose slowly, and it had reached the Siang.

In jubilation, it sprang towards the Siang, ending its grand feat, only to find the river greyer than an ageing granny’s hair, doused with liquid cement. The smelly ashen water entered its wounds and orifices, blinding it. Was he in a dream? Was it in the spirit realm?

But alas! It was not lucky to join its family in the afterlife.

It woke up, flapped its tail and fins, and tried to go back to the grey gruel.

But the catfish found itself unable to breathe and swim potently against the water currents. He was changing.

The strong currents had taken it to a shore where it discovered that it had turned into a man. The fins were replaced with hands, the tail with two legs, and the whiskers transfigured into a thick and lengthy moustache that touched its feet and even the ground beneath it.

The catfish was now a naked pitiful man, a strange worm between his thighs. The slender tail was gone, exchanged for two twig-like legs. He felt thirsty, no more slime for protection, his body now expelling, covered with salty water. Unable to balance himself on the two twigs, he fell again, and again, until he learned to stand.

/// \\\

A woman came that morning to the very same shore where the catfish had landed. She had a net and a woven bamboo fish basket and was there early to try her luck. She had some fish in the basket, which the naked catfish peeked at, as he achieved fluency in walking. She was busy adoring her catch and left the naked man unnoticed. He hadn’t had anything to eat, so he moved towards her in fury. The basket was snatched away from the woman in an ambush by the catfish-turned man. The woman, thinking the naked catfish was a perverted flasher, screamed and smashed her net on him. The naked man fell, and the woman took the moment to flee in a hurry, leaving a slipper behind as she ran away.

The naked catfish regained its balance and ventured forward to the settlement near the bank. It was drawn towards the settlement after smelling pig waste in the air, which strangely attracted him. Now the pig waste was the fallen fruit in Sita-Pong for him, he had lost his mind, what smelt or tasted good, nothing mattered. He was still under the influence of the Siang’s grey water, half-blinded and confused. He moved towards the elevated pigsty and started eating the pig waste that fell from it. He stuffed his mouth with the waste, some hardened as pebbles, other in the consistency of rice porridge and majorly decomposing matter with potent piss fragrance, the waste was coming out from his nose, he was vomiting out some, yet he continued to ingest back all of it, and after reaching his capacity, he moved forward, straying away from the bank of the Siang.

It had become a fine sunny day. Tajong, the clerk at a primary school, had taken a sick leave to fish in the Siang but found the water unsuitable for fishing. It seemed that every fish in the Siang had died in this gruel. He was also returning from the shore on the same road as the naked catfish. The catfish saw Tajong coming back with his fishing regalia. Blinded by its sense of smell and hearing, and unable to see properly, it thought Tajong was another fish carrier. The catfish-man ran towards Tajong, who saw this naked man charging towards him and swung a fist at the catfish’s face. Tajong had heard about these perverts inhabiting the jungles and remote locations but never thought he would encounter one. The catfish regained his senses and sprang on Tajong again, the wedding ring he had worn slipped and the catfish-turned man swallowed it. Tajong wrestled with the catfish and threw him onto the dry riverbed before fleeing the location in fear. As he fled, the rain clouds arrived and burst with vigour, filling the dry riverbed. Finally, the season of rejuvenation had come for the Sibo-Korong. The rain washed the layer of grey gruel from the catfish’s anthropoid body, and it transformed back into its old self of a humongous catfish with long whiskers. As it regained its senses, a net was cast over it. The net of a fishmonger who never missed an opportunity to increase his profit, fishing not just from the fisheries but from drains, rivers and protected zones. Anywhere where a big catch could be caught.

/// \\\

Tajong came back home, short of breath. He was faint and dropped his fishing regalia on the doorstep. His wife, Opi came to his rescue, fanned him, and gave him the much-needed water to drink. “What happened to you?” she questioned with concern. Tajong didn’t say a word. Opi remarked again after noticing Tajong’s empty fish bag, “I told you! You won’t find any fish in the Siang. My brother told me yesterday about the water condition. I told you, but you didn’t listen to me.” Tajong, who was regaining his senses, said, “Yes, indeed.” Opi, with a jolly tone, said, “No worries, I asked the fishmonger Balleshwar to get a catfish from his pond.” After saying this, Opi went to her backstrap loom to work on her sarong and directed Tajong to degut and cut the fish for lunch. Tajong did as directed by his wife. He slit the stomach, from which came out undigested fish and faeces. He unwillingly threw these out. “Opi, what kind of fish have you bought? It stinks, I don’t want to de-gut it! Opi take over, love.” Tajong yelled in irritation. Opi reluctantly cleaned and deep fried the fillet. Tajong now noticed his lost ring, but he didn’t complain fearing yelling from Opi, who had previously chastised him for losing a ring. As Tanjong silently took the bite off a fillet, he bit on something stiff; he spat out the food, discovering his ring.